Women in Trouble: Sexual Violence as the Ultimate Evil in David Lynch’s Twin Peaks

How trauma, memory, and complicity shape the moral universe of Twin Peaks

Few things have stayed with me like Twin Peaks: The Return. Not an original feeling, but true, nonetheless. The series is dream-like and abstract, built with scenes and moments that are unlike anything else on TV, before or since. But that’s not the reason The Return has stayed with me. It’s the deep unease that accumulates over the eighteen-hour run time, a spiral born from the original sin of Twin Peaks: not the murder of Laura Palmer, but the complicity of Laura Palmer’s friends, family, and acquaintances in the trauma and abuse Laura Palmer endured throughout her life.

In Twin Peaks, David Lynch and Mark Frost position sexual violence as the ultimate evil—so absolute, its traumatic aftershocks ripple throughout decades, warping time, identity, and reality itself. An even more disturbing implication of The Return, however, is that the forces aligned against that evil are willing to exploit the trauma sexual violence creates as a necessary instrument of containment.

I’m not the first to read Twin Peaks through this lens, nor do I claim this interpretation as definitive. But it is the understanding that has kept the series alive in my subconscious, even when I’ve gone years between revisiting it. Episode by episode, The Return feels like it’s circling a single wound—Laura Palmer’s—and treating it as a cosmic event. Not in the sense of destiny or chosen-one mythology, but in the way certain tragedies create psychic aftershocks that never stop propagating. The show’s central horror isn’t simply that Laura was murdered. It’s that she was violated, repeatedly, by a force that hides inside the familiar. Murder ends a life; sexual violence colonizes it. And in Lynch’s universe, that colonization is metaphysical.

The image Lynch can’t stop re-staging

Despite being famously reluctant to explain his work, Lynch has often described a defining childhood memory: seeing a naked woman walking down the street, crying, in a dazed, terrified state—an image that haunted him and never left.

If you want a single “seed image” for Lynch’s work, it might be that: a woman exposed, unprotected, moving through a normal neighborhood as if the world has failed to keep its most basic promises. That figure reappears, transformed, across his filmography—not always literally naked, not always literally running, but consistently in trouble: endangered, disoriented, pursued, fragmented, or trapped inside someone else’s desire.

When asked what Inland Empire is about, Lynch simply offered: it’s “about a woman in trouble,” and it’s a mystery. “A woman in trouble” isn’t just a tagline; it’s a lens.

Seen through that lens, Twin Peaks: The Return reads like the culmination of a lifelong theme—and perhaps the most uncompromising version of it. The original series flirts with the idea that a town can be haunted by the secret exploitation of women. Fire Walk With Me makes that exploitation explicit. The Return goes further: it implies that the exploitation is not only necessary to sustain evil, but it’s also the fuel that “good” quietly runs on.

Laura as counterforce—and as sacrifice

Part 8 of The Return reframes the entire mythology: we witness the atomic test give birth to a new kind of evil in the world with the creation (or release) of BOB—the evil entity that possesses Leland Palmer for the purpose of repeatedly assaulting his daughter, Laura.

The rise of BOB inspires a counter-response from forces of good represented by the Fireman. Existing in another plane of existence or metaphysical space, the Fireman produces a glowing orb containing Laura Palmer’s face—an act presented with the solemnity of creation, not metaphor. This sequence is the foundation for the common reading that Laura is a kind of cosmic countermeasure: a light introduced into the world as an antidote to a newly intensified darkness.

But even if we accept the countermeasure reading, the ethical question doesn’t go away—it intensifies. Because the Fireman does not create Laura and then protect her. He does not place her outside harm. He sends her directly into it.

Part 8 reframes our understanding of Laura Palmer. She wasn’t a victim of BOB’s evil by chance. Instead, she is set on this path as a cosmic antibody to absorb and bind the toxins unleashed by the atomic test. The Fireman never intends for her to annihilate BOB but contain it. In human terms, that means Laura is designed to receive what the world cannot otherwise metabolize.

If sexual violence is the ultimate evil in this universe, then Laura is created to face it head-on—not as a chosen one or warrior, but as a vessel. And that’s the first major jolt of The Return: the “forces of good” are more than willing to let a girl be destroyed if her destruction keeps darker forces at bay.

Cooper’s arc: from protector to instrument

This is where Dale Cooper becomes the most tragic and unsettling figure in the series—not because he fails, but because success in this world resembles complicity.

After traveling back in time to prevent Laura’s death, Cooper has to complete the second leg of the mission given to him by the Fireman. Here, he crosses a threshold in another dimension and is no longer the warm, curious agent who arrives in Twin Peaks with wonder and decency. He is a man moving through coordinates, instructions, doorways—operational language that sounds less like investigation and more like ritual. The Fireman’s directives (“430,” “Richard and Linda”) feel like mission parameters rather than guidance, as if Cooper is a piece being moved across a board.

As part of this mission, Cooper must have sex with Diane, who was revealed to have been raped by Cooper’s doppelganger, Mr. C, in the 25 years between the original series and the revival. The sex scene plays like a ritual: cold, relentless, strangely grief-stricken, as if intimacy has been stripped of connection and repurposed as a mechanism. To enact the next stage of the Fireman’s plan, Cooper must willingly traumatize Diane as the Fireman was willing to traumatize Laura.

This adds to the unnerving sense that for all its quirkiness, The Return is about the exploitation of women’s pain as a tool against evil. And that Cooper is either a misguided white knight or a complicit operator inside the metaphysical machinery that drives the battle of good versus evil between the Fireman and Judy (the evil entity that spawned BOB).

The finale as retraumatization

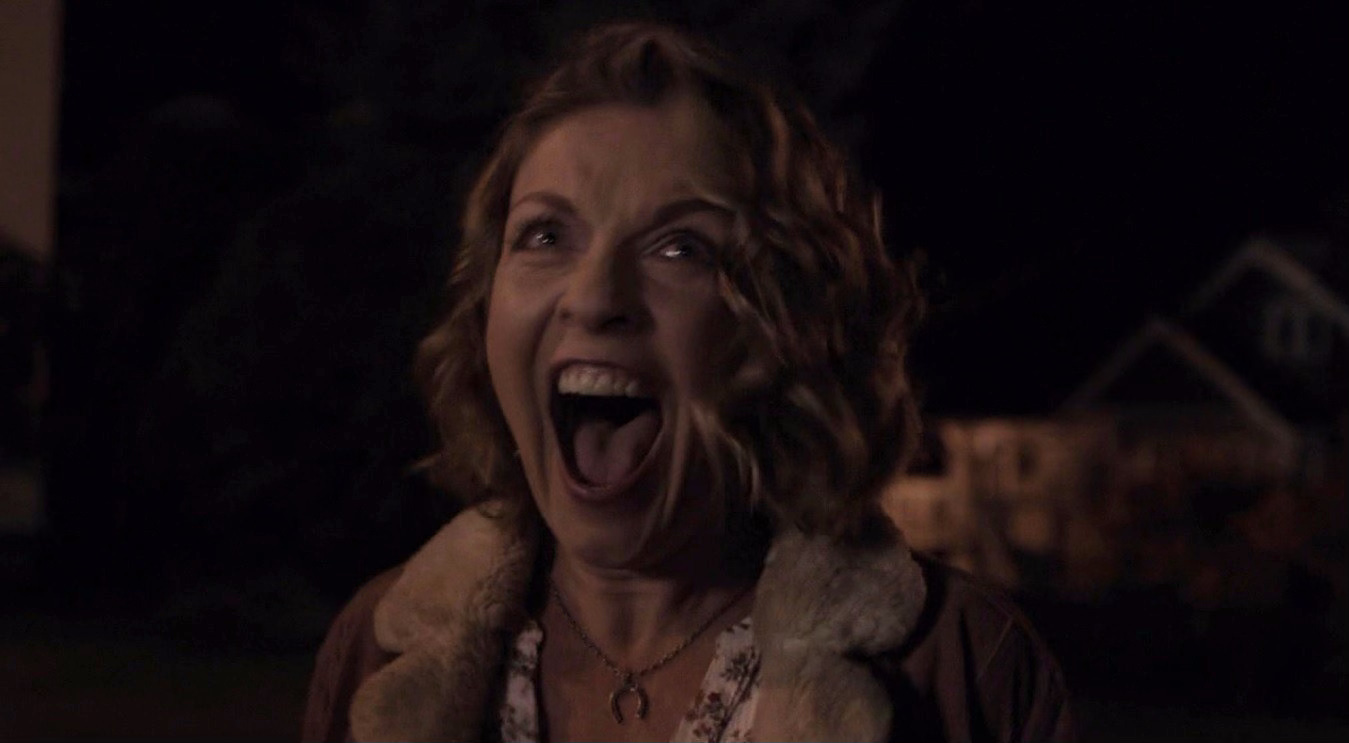

In Part 18, the finale, the Fireman’s directives have Cooper retrieve an alternate Laura (Carrie Page) and bring her back to the Palmer house. Once there, the voice of Sarah Palmer (Laura’s mother, who’s been established as a vessel for Judy) calling her name echoes across dimensions, reactivating Laura’s trauma until it erupts as a scream that short-circuits the electricity—the show’s recurring symbol for Lodge influence and malignant presence.

Cooper doesn’t guide Carrie gently toward self-knowledge. He takes her to the scene of the crime for the purpose of, whether he’s aware of it or not, retraumatizing her.

The result is a complete electrical blackout in this alternate dimension Cooper’s created; trauma discharged so violently it extinguishes the electrical channel evil travels through—neutralizing Judy. A loss for the forces of evil, a win for the forces of good.

But at what cost?

In its final moments, Twin Peaks: The Return makes one thing clear. Cooper’s mission was never about saving Laura from the trauma she experienced. His mission was about saving her from death so she could fulfil the Fireman’s original mission: using her trauma to overload the evil forces that feed on “garmonbozia”—also known as “pain and suffering.”

Audrey: a wound metastasizing

Audrey Horne’s fate is one of The Return’s most revealing cruelties. Her storyline, introduced midway through the run, plays as a series of vignettes disconnected from the rest of the season. In these vignettes, we watch her argue in circles, pursue an absence (“Billy”), swing between moods, then arrive at the Roadhouse for a moment that feels like pure nostalgia—Audrey dancing to Angela Badalamenti’s score, an echo of a memorable scene from the original series.

The nostalgia is disrupted when a fight breaks out in the Roadhouse. Audrey wants to go home. But she can’t. The scene fractures, and Audrey wakes in a sterile white room. An electrical crackle can be heard as she looks in a mirror, as if discovering she has been living inside someone else’s idea of her.

The show frames Audrey as someone whose identity has been shattered by forces she cannot name. Mark Frost’s The Final Dossier clarifies the grimmest implication of The Return: Audrey was raped by Mr. C, and Richard Horne is the product of that assault—evil reproducing through sexual violence.

Like Laura and Diane, Audrey becomes another woman whose life is not simply damaged, but reorganized around assault, with reality itself bending in response. Audrey’s final state isn’t just sadness; it’s derealization, the sense that she’s no longer the plucky teenager she once was. Trauma, here, doesn’t live in memory; it shapes the environment.

If Laura is the original wound that haunts Twin Peaks, Audrey is the proof that the wound metastasizes.

Psychic aftershocks

In The Return, Twin Peaks the town no longer feels like a quirky community with a darkness beneath it. It feels like a place living after tragedy. People aren’t merely changed by time; they’re flattened by it. Their conversations have the drained quality of lives lived adjacent to something unspeakable for too long.

The Return presents the town as if it is still reverberating with Laura’s psychic trauma. The violence is not back. It never left. The community simply learned to live inside the echo.

This is illustrated in one of the most controversial scenes in The Return: the extended floor sweeping scene at the Roadhouse.

Lynch holds on a person sweeping the floor for what feels like forever. What initially presents as one of the most frustrating and indulgent scenes in The Return is key to my understanding of the show. The sequence is punctuated by the Roadhouse’s owner taking a phone call that confirms the world of prostitution and trafficking that exploited Laura Palmer is still alive and well in the town of Twin Peaks.

Sweeping the Roadhouse is as mundane and business as usual in Twin Peaks as pimping and trafficking. The broom becomes a metronome. The moral horror isn’t that these things happen—it’s that the town has done nothing to address the rot that contributed to Laura’s tragedy in the intervening 25 years.

This is Twin Peaks in miniature: the dance floor, the music, the community vibe—and, underneath, the continuation of the pipeline that led Laura to her fate in the first place.

The Roadhouse: where dreams bleed into reality

Which brings me to the Roadhouse—the show’s most deceptively simple recurring device, and the clearest barometer of the season’s spiritual weather.

Almost every episode ends with a Roadhouse performance, a coda that’s part concert, part Greek chorus, part dream diary. The musical arc of Twin Peaks tracks the season’s journey from nostalgia as bait, to a kind of communal trance, to outright foreboding that the crowd absorbs without protest.

At the end of Part 2, Chromatics’s “Shadow” plays like a seductive opening gambit: the show handing you mood, melody, familiarity—an invitation to sink back into the familiar nostalgia of Twin Peaks.

As the season darkens, the Roadhouse becomes less a comforting venue and more a threshold. Nine Inch Nails’s “She’s Gone Away” appears in Part 8, the episode that stages the atomic bomb as a metaphysical rupture. The performance doesn’t feel like “a band playing a song.” It feels like an invasion of industrial dread into the town’s bloodstream—an announcement that the old dream has been contaminated.

Later, in Part 15, The Veils perform “Axolotl,” and the show overlays the performance with a violent removal of a woman (Ruby) from her booth—her screams cutting across the music, evoking the various times Laura has screamed through the series. This is Lynch using music as enchantment, violence as interruption, the crowd continuing to exist inside the vibe as if the vibe matters more than the horror.

That indifference—people swaying to ominous music while evil proliferates—becomes the point. The Roadhouse crowds often look ambivalent, half-hypnotized, present in body but oblivious to the stories unfolding around them. In that sense the Roadhouse is not just a setting. It’s a litmus test for what the town can absorb without changing course.

Critics and commentators have described the Roadhouse as liminal—an in-between space where the show’s reality drifts closer to dream logic. The Roadhouse is where The Return tells the truth in emotional code. The plot is often cryptic; the music is not. Each performance is a mood prophecy.

Nostalgia first. Then unease. Then dread. Then numbness. Then rupture.

The Return as a culmination

If Blue Velvet is the discovery that violence and sexual exploitation live beneath manicured suburbia, then Lost Highway is the realization that identity can fracture under that pressure. If Mulholland Drive is the dream of Hollywood collapsing under the weight of betrayal and humiliation, then Inland Empire is the nightmare of a woman disappearing into roles, rooms, and violations—“a woman in trouble” multiplied into a labyrinth.

Twin Peaks: The Return feels like Lynch pulling on all these threads at once—using the Twin Peaks mythos as the apotheosis of the stories inspired by the childhood memory of a terrified woman, exposed to a world that won’t protect her.

And the decisive thing The Return does—what makes it feel like a period at the end of a lifelong sentence—is that it refuses any comforting separation between evil and resistance. It suggests that in a universe where sexual violence is the ultimate evil, there may be no clean way to fight it. There may only be bargains, sacrifices, and containment strategies that reproduce the very harm they claim to oppose.

That’s why the ending doesn’t feel like closure. It feels like an indictment.

Cooper stands there, confused, as if he’s completed the mission and only now realizes what the mission was. Carrie/Laura screams, and the house goes dark, and the series ends in a silence that doesn’t feel like peace.

In Twin Peaks, the scream is the thesis.

It isn’t just fear. It’s recognition. It’s memory flooding back. It’s the psychic echo of sexual trauma returning with enough force to disrupt the circuitry of evil, while also proving that trauma can’t be solved with a quick fix, it can only be displaced.

And that displacement—women’s pain redirected, repurposed, turned into a tool—is exactly the thing The Return can’t stop showing us.

Not to shock. Not to moralize. But to force a question that lingers long after the screen goes black: If the world requires women to suffer in order to keep evil contained, what kind of world is that—and what, exactly, is the difference between good and evil?